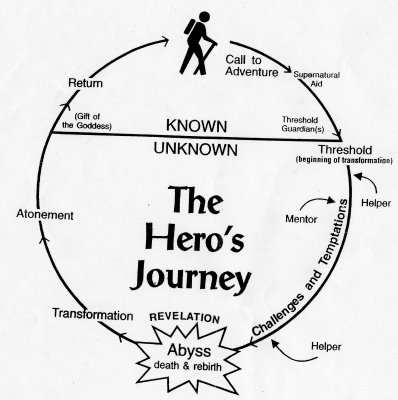

Campbell writes that the hero's passage into this stage of the journey can often be mistaken by the casual observer as defeat: "The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died. This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation. Instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again. The disappearance corresponds to the passing of a worshipper into a temple – where he is to be quickened by the recollection of who and what he is, namely dust and ashes unless immortal. The temple interior, the belly of the whale, and the heavenly land beyond, above, and below the confines of the world, are one and the same. . . The devotee at the moment of entry into a temple undergoes a metamorphosis. Once inside he may be said to have died to time and returned to the World Womb, the World Navel, the Earthly Paradise. Allegorically, then, the passage into a temple and the hero-dive through the jaws of the whale are identical adventures, both denoting in picture language, the life-centering, life-renewing act.""

Examples of the Whale's Belly

The quintessential example of the Whale's Belly comes from the Biblical story of Jonah. Commanded by God to preach to the city of Nineveh, the prophet Jonah instead ran the other direction, boarding a ship sailing for Tarshish. Along the way, a great storm blew up and threatened the ship. Jonah was revealed as the source of the calamity when the sailors cast lots to discover who among them had incurred the wrath of the gods. Accepting responsibility and seeking to spare the ship, Jonah had the sailors throw him overboard, where he was swallowed whole by a great fish, almost always visualized as a whale. He remained in the fish for three days and three nights, praying to God. Finally, Jonah was vomited onto dry land and, when commanded by God to go to Nineveh a second time, did not delay. The city, destined for destruction due to their evil ways, repented as was spared.

Luke Skywalker's metamorphosis experience is stretched across one movie, and nearly into a second. Over the course of Empire Strikes Back, shortly after being - quite literally - stuffed inside a Tautaun's belly (womb allegory), he heads to swampy Dagobah to train with Yoda, who lives in a cramped little hut (another womb). It is here that he truly sees for the first time what the Force is capable of. It is also during this training that he has a disturbing vision in a cave (yet another womb allegory) about what could happen if he failed to resist the lure of the Dark Side. By the end of Empire Strikes Back, Luke's metamorphosis has taken on a physical aspect in the hand that is lost and subsequently replaced. The changes and growth he experiences during the course of this movie carry him into the period between the fifth and sixth chapters, during which he becomes a full-fledged Jedi.

Despite several close calls with the Nazgul, who appear as nightmares given form to the diminutive hobbits, it is within the mines of Moria that the Frodo, Sam, Merry, and especially Pippin have a transformative experience. As they pass through the depths of the mountains, they find themselves for the first time face-to-face with goblins (subterranian orcs), a troll and (most terrifying of all) a Balrog - all due to Pippin's carelessness in Balin's Tomb. This is the first encounter where the hobbits must hold their own, along with their more traditionally heroic companions, lest they be overwhelmed - there would be no last-minute rescue for them as their was with Old Man Willow and on Weathertop. Eventually, the group escapes, but not before the harsh reality of their situation is made all too clear with the loss of Gandalf. The movie, specifically, Billy Boyd's portrayal of a guilt-ridden Pippin as the fellowship succumbs to exhaustion and anguish by the Dimrill (East) Gate.

In the first act of Christopher Nolan's excellent Batman Begins, Bruce Wayne makes his way to the League of Shadows' compound in the mountains of Tibet. There he undergoes intense martial and psychological training in order to, as Liam Neeson's character put it, "make yourself more than just a man, devote yourself to an ideal, and if they can't stop you, then you become something else entirely . . . A legend."

Belly of the Whale as a DM Tool

DM's (or should I be using GM's instead?) regularly make use of this concept, though probably not in such a formal, recognizable manner. Basically, any time the PC's must acquire crucial knowledge and/or abilities in order to complete a task deemed by the common folk to be impossible, the Belly of the Whale comes into play. Their time in the Belly-setting answers the where and how questions about what the PC's need to accomplish in order to be victorious.

There a couple of common temptations that a DM faces during this stage: First, glossing over the metamorphosis experience - making it happen instantaneously, thereby robbing it of meaning; and, second, requiring the PC's to grind until they have accumulated enough of a resource (gold, XP, specific dropped items) as a symbol of their completion of the metamorphosis process. This second scenario is particularly frustrating because it assumes that by doing the same thing over and over again, the protagonists have somehow matured or mastered a new way of thinking/fighting - when the reality is that they have simply gotten better at doing the same thing over and over again.

Setting is important to the metamorphosis, there is something unique about it that is crucial to the changes that need to occur before the PC's can hope to overcome the trials ahead. It makes sense, then, that there is also something repulsive about the location or the process related to the metamorphosis that deters just anyone from pursuing it - perhaps it is in a location that is dangerous to reach, or the metamorphosis process is a painful - even potentially deadly - experience. Perhaps there is a characteristic about those who have completed the change that is perceived, fairly or unfairly, as unsettling or even dangerous. The concept of a reviled savior is an interesting one and holds a lot of potential for true role playing.

Pondering the Belly of the Whale

- What sort of settings do you envision when you think about undergoing a change or experience growth?

- Is the change that occurs in the Belly of the Whale permanent or temporary? Why?

- Do you tend to think of the metamorphosis process as being a result primarily of external or internal forces?

- Can a hero be committed to vanquishing the dragon, but hesitant about what must be done to accomplish such a task? Why or why not?

- Should a metamorphosis be specific to a single quest? Do relying on a specific change across multiple adventures 'cheapen' it? Why or why not?

Once the hero - by hook or by crook, consciously or unconsciously - begins to undertake his quest in earnest, they usually do not have to wait very long before a guide or magical helper of some sort is introduced into the story. The arrival of supernatural aid in fantasy literature is such a common occurrence that fans of the genre are generally more surprised when it does not occur. Consequently, the event is often taken for granted and treated as little more than a plot device - a means by which the hero obtains possession of some trinket or knowledge they would (or could) not gain on their own.

Once the hero - by hook or by crook, consciously or unconsciously - begins to undertake his quest in earnest, they usually do not have to wait very long before a guide or magical helper of some sort is introduced into the story. The arrival of supernatural aid in fantasy literature is such a common occurrence that fans of the genre are generally more surprised when it does not occur. Consequently, the event is often taken for granted and treated as little more than a plot device - a means by which the hero obtains possession of some trinket or knowledge they would (or could) not gain on their own. In Tolkien's Ring's Trilogy, Gandalf metamorphoses before Frodo's eyes from a wizened old conjurer to a mighty wizard, mentor, and protector. He identifies the One Ring the Bilbo left to Frodo (which, I'll admit, is not exactly the same as giving it to him), guides and protects the Fellowship from a demon in the darkness and death of Moria ("I am a servant of the Secret Fire . . ."; flame ~> Holy Spirit -> God), returns from the dead (!), arrives just in time to save Rohan at Helm's Deep, bolsters and leads the forces of Gondor until Aragorn can arrive with even more supernatural reinforcements, and flies into Mordor on Gwaihir to rescue Frodo and Sam.

In Tolkien's Ring's Trilogy, Gandalf metamorphoses before Frodo's eyes from a wizened old conjurer to a mighty wizard, mentor, and protector. He identifies the One Ring the Bilbo left to Frodo (which, I'll admit, is not exactly the same as giving it to him), guides and protects the Fellowship from a demon in the darkness and death of Moria ("I am a servant of the Secret Fire . . ."; flame ~> Holy Spirit -> God), returns from the dead (!), arrives just in time to save Rohan at Helm's Deep, bolsters and leads the forces of Gondor until Aragorn can arrive with even more supernatural reinforcements, and flies into Mordor on Gwaihir to rescue Frodo and Sam.

Setting off a trap on your girlfriend is not going to win you any brownie points.

Setting off a trap on your girlfriend is not going to win you any brownie points.